History of Rose Croix

The ‘Rose Croix’ Degree is the 18th of a series of 33 degrees, originating in France and which in 1801 were formed into the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry.

By the 1600s, some lodges no longer had any working stonemasons and were instead filled only with gentlemen engaged in moral, scientific, and social pursuits. In 1717, when London’s four pre-eminent lodges met at the Goose and Gridiron alehouse in St Paul’s churchyard to establish the first Grand Lodge, there was already a sophisticated and widespread network of masonic lodges up and down the country.

In time, other groups of masons appeared, many holding themselves out as the next level, as alternatives, or even as rivals. In wider society, there was simultaneously a burgeoning of other, non-masonic moral and philosophical societies, like the Rosicrucians with their hermetic wisdom, or the Bavarian Illuminati with their anti-obscurantism. It was the age of the fraternity, in which the 1600s and 1700s saw English (and then British) people fanning out across the world to engage in exploration, trade, travel, and settlement. They took masonry with them and, before long, there were lodges from the Americas to the East Indies.

By the mid-1700s, systems of masonry known as Hauts Grades (High Grades) had begun appearing in England then Europe, often referencing Scotch, Scots or Scottish degrees (confusingly, there is no connection to Scotland). Unlike most masonry, these dealt with themes other than Hiram, Noah, and the Old Testament, instead moving into the New Testament and medieval worlds. In a deeply divided and bloody century, there was also a political element. When the Hanoverians stamped their mark on Craft masonry from 1714 onwards, the Hauts Grades became, for a while, associated with the Jacobites.

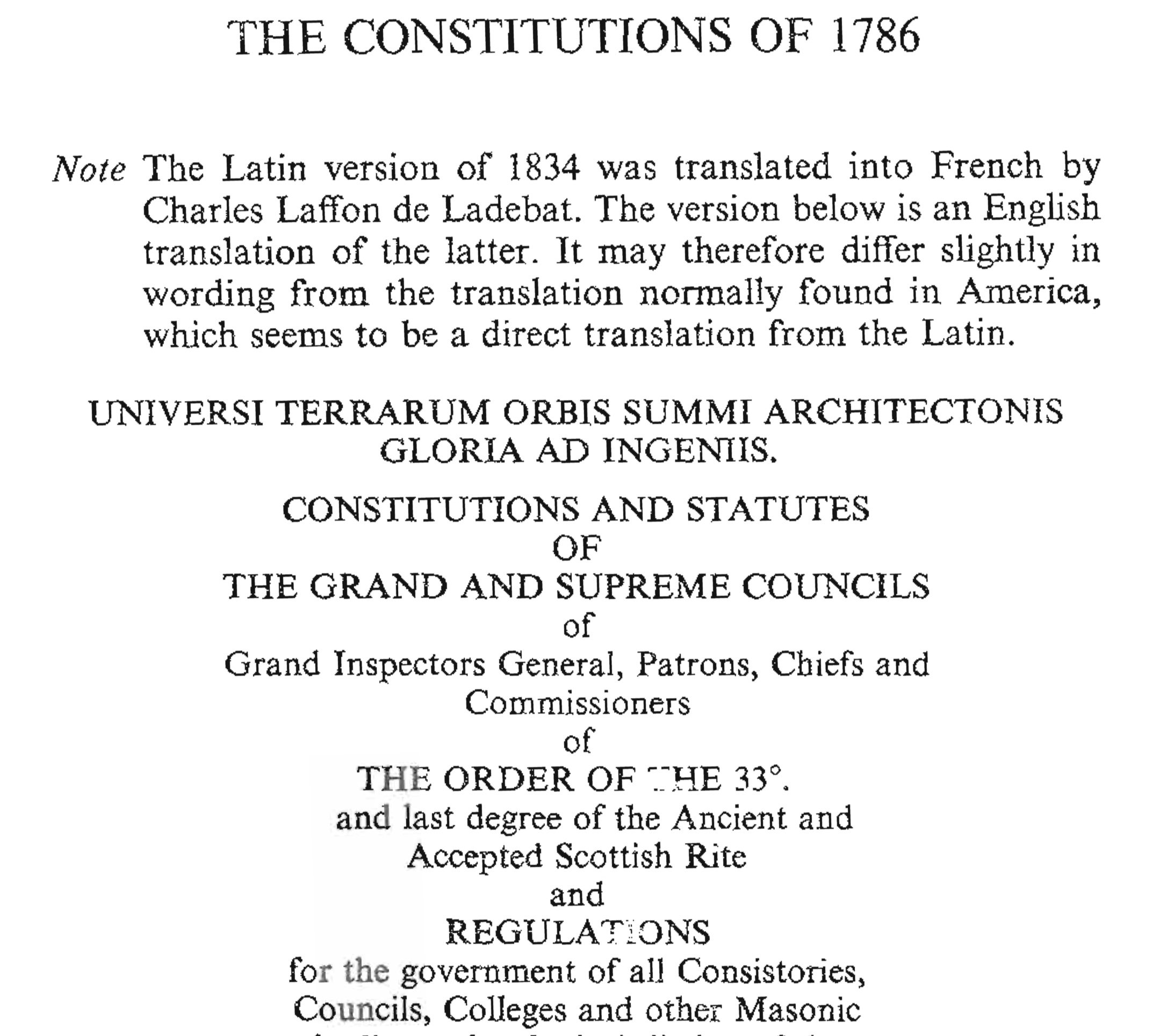

The popularity of these Scottish degrees meant there were soon attempts to organize them, with the most important development being the emergence of a constitution published in French and Latin in 1832 under the motto Ordo ab chao (order from chaos). Partial rules had appeared piecemeal before that date, and there was even talk of an original Constitution signed by Frederick the Great of Prussia in 1786, but it was a grandiose fiction.

18° Collar & Jewel

30° Sash, Jewel, Collarette & Jewel

31° Collar, Jewel, Collarette & Jewel

32° Collar, Jewel, Collarette & Jewel

33° Sash, Jewel, Collarette & Jewel

This Constitution is the governing document for what is now the Ancient and Accepted Rite (AAR for short), administered in each jurisdiction by a Supreme Council. The oldest is the Supreme Council of Charleston, South Carolina, which dates to 1801, just a few decades after the independence of the United States. Before long, there was also a Supreme Council in the northern United States, and many distributed across Europe.

The AAR arrived in London in 1845, where a Supreme Council for England and Wales was chartered by the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction of the United States of America. Today, this Anglo-Welsh Supreme Council is based in Piccadilly, from where it oversees its districts and chapters in Britain and overseas. Most English and Welsh masons simply refer to the AAR as the ‘Rose Croix’, although this is, technically, the name of only one among its degrees.

Unlike most masonic orders, the AAR does not offer just one or a few degrees. The Constitution fixes the number at 33 degrees, which together provide an entire, self-contained system of masonry. In England and Wales, the United Grand Lodge of England’s three degrees of Craft masonry are seen as equivalent to the AAR’s first three degrees, after which the AAR offers another 30 that take members through a kaleidoscope of masonic rituals and philosophy.

The ‘Rose Croix’ in England and Wales remains a uniquely loved order among its members, for whom it reaches back into the vivid, colourful imagery and legacy of masonry’s medieval past. It draws on the symbolism of the worlds of the cathedral and castle, of pilgrim and knight, in exquisite degree ceremonies that are quite unlike any other system of masonry. They offer a richness of history and meaning that not only enhance the member’s experience of masonry, but also provide a continuity with the High Grades and Scottish masonry of the turbulent 1700s, giving the degrees a unique DNA and historical vibrancy. The AAR calls itself the ne plus ultra and Perfection of Masonry which, to many of its members, it always will be.